Celebrating 200 years

To begin, we need to grasp the reality that our concept of what constitutes a trade association today is far different to how it commenced in the late-Georgian Ireland of 1817.

To understand the origins of the Fair Trading Vintners Society and Asylum (founding name) we must firstly restrain from retrospective analysis and judgement based on the materialistic barometer of today; in other words, as a prerequisite to entering the spirit of that distant age, we must set aside the contemporary global preoccupation with economics, statistics, market research and branding. These values, in so far as they existed back in 1817, would have been considered unworthy, base, ignoble and devoid of integrity. In clear contrast, the guiding motives of the Association’s founding fathers were standards of honour, principle, justice, integrity and ethical responsibility.

Foundational Aims

The FTVS&A founders primarily wished to establish themselves as a legitimate, reputable and responsible association and to be recognised as such within 19th Century society. In an era when licence-holders sometimes traded for a day and disappeared overnight – there were many unlicensed outlets and ale wives produced brews of disturbing gravities (sometimes from contaminated water) – the licensed trade needed legitimacy, authority and consistency.

There was equally a decided altruistic aspect to the Association’s foundation – the principals wished to address the impoverishment that had befallen publicans through mortality, ill-fortune and bankruptcy. The asylum aspect of the association set out to accommodate widows and children – particularly the orphans – of publicans who’d fallen on hard times.

Self-funded, devoted to the Society

The early association was totally self-funded to meet the liabilities of the age. Meeting in one another’s premises on a weekly basis, members unselfishly gave of their time to meet the emerging challenges. The largest challenge always arrived via increased imperial taxation and whenever the British had a war or a military skirmish, they expected the licensed trade to pay in extra taxation. Without an independent parliament since the passing of the Act of Union (1801) all laws pertaining to Ireland were legislated from Westminster, frequently in a manner that was both unsympathetic and punitive. As a consequence Irish economic life floundered. But the FTVS&A’s founding fathers – notably Andrew Luke, John Eiffe and William Fitzpatrick (Davy Byrne’s) – were driven by a passion that sought to attain fairness and justice for the legitimacy of their cause. They frequently left their pubs late after work, travelled by ferry through the night to England and made the hazardous road journey to London – all at their own personal expense. Having arrived there they made their way to the House of Commons or Lords and waited – sometimes for several days – in the lobby to meet the relevant Treasury Minister whose decisions threatened their livelihood.

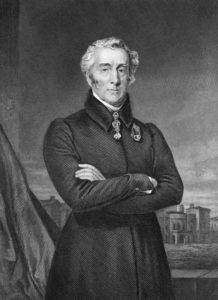

In 1830 the vintners had a notable success in that they persuaded the Duke of Wellington to drop a proposed spirits tax increase that would have crippled the irish licensed trade.

The origin of Lobbying

On one such historic occasion in 1830 the vintners had notable success in that they persuaded the then Prime Minister, Dubliner The Duke of Wellington, to drop a proposed spirits tax increase that would have crippled the Irish trade. The British papers reported this as a capitulation by the government and a victory for the “lobbyists” – literally, the people who waited in the lobby. It was a landmark success for the LVA’s founding fathers – and a new word for the English lexicon.

The scourge of dram drinking

Throughout the 1830s and 40s the licensed trade perpetually struggled against unfair competition emanating from grocer’s shops through the illicit practice of dram drinking. Customers to grocer’s shops bought spirits and consumed them illegally behind makeshift screens (despite the fact that grocers were not permitted by law to hold spirit licences). Outraged vintners, who ran legitimate licensed establishments, lobbied both the drinks industry in Ireland and parliament at Westminster.

The increasing tension led in 1838 to a bitter fallout with The Liberator, Daniel O’Connell, whom the vintners had earlier been instrumental in electing to parliament at Westminster. O’Connell had stated that “all the evils of excessive drinking and debauchery emanated from Public Houses and not from Grocers Shops”. But O’Connell, who was no stranger to debauchery himself, had a particular conflict of interests in that his son ran the Phoenix Brewery in James’s Street.

“All the evils of excessive drinking and debauchery emanated from Public Houses and not from Grocers Shops” – Daniel O’Connell.

The Temperance Era

Bad news followed bad news for the FTVS&A in that following the passing of The Irish Spirit Licensing Bill (1838) under which grocers could now legally acquire spirit licences a new source of challenge was sweeping through the country. Capuchin priest Fr Theobald Mathew, whose family fortune was gained from the distilling industry, began a nationwide reforming crusade against the consumption of alcohol.

Converting millions to his cause, Fr Mathew was responsible for a social demise that witnessed 2,000 publicans nationally enter bankruptcy over a five-year period and a reduction of revenue to the Exchequer from £1,435,000 in 1839 to £352,000 by 1844.

Old enemies unite

The long-running grocers’ and publicans’ civil war ended peacefully in 1862 when the two bodies merged to form a new association, the Licensed Vintners and Grocers Association. Evidence of that union remains visible throughout Ireland today – you frequently see a grocer’s shop in one section of the premises and a bar in another.

The Victorian pub

A creation that originated in the larger cities of England during the Second Industrial Revolution, the Victorian pub soon spread to Ireland where it found a lasting home especially in Dublin. LVGA inspirational publican and chairperson Daniel Tallon (Whelan’s of Wexford Street) led the campaign for publicans to upgrade their premises, distinguish themselves from the fly-by-night operators – who held beer house licences at one shilling per annum – and attract the reluctant and prudish middle class Victorians into their pubs. The results were phenomenal in what was becoming a boom period for the Irish pub.

The early 20th Century

By the dawn of the 20th Century Ireland was contributing £3 million to the Exchequer per annum in excess of her just proportion of imperial tax. The largest proportion of this came from the combined drinks industry. However these were also good times as the number of licences had increased annually since the 1880s. On the lobbying front the trade had magnificently negotiated and resisted the British Temperance campaign for compulsory Sunday Closing whereas both Scotland and Wales had failed. Scotland also had Early Weekday Closing and England had pledged to introduce both within the spirit of the law.

1917 Centenary

If the association had envisaged a glorious Centenary the dream quickly soured. The First World War brought enormous challenges both in vastly increased taxation on spirits and beer and severe restrictions on brewing and distilling. By 1917 the licensed trade was literally under siege: massive tax increases, sparse supplies because of the war effort, daily pub closures, restrictions on brewing gravities, higher wage demands and great political unrest throughout the nation.

The trade organised a Monster National Protest Meeting in the Phoenix Park on August 22nd attended by between 25,000 and 50,000 depending on estimates. The British momentarily took notice and set up public hearings within The Liquor Trade Finance Committee (Ireland) 1917 at Westminster. Both the Power and Jameson distilling families notably supported the trade in its submissions.

20s and 30s – strikes and repressive legislation

While Ireland had secured her ancient goal of national independence, these were lean years for the licensed trade because of the impact of two bar strikes. Additionally, repressive legislation by the incumbent Free State Justice Minister Kevin O’Higgins had reduced both opening times and the number of licences nationwide. As a consequence the trade issued a recommendation on November 27th 1926 that members should cease association with all political parties.

Lean times, better times

Following the decline in economic and agricultural activity throughout the Economic War with Britain the State relied heavily on taxation from the drinks industry as its major source of revenue. In many respects the licensed trade was the goose that continued, year after year, to lay the golden egg. Despite annual hikes in excise duties De Valera’s governments ensured the ‘goose’ remained in relatively good health.

A new more adventurous age dawned for the licensed trade in the 1960s with relaxation in the licensing laws, the arrival of the lounge bar and the most welcome advent of women into the Irish pub. This was followed by the arrival of the carvery lunch and the pub food revolution. Good times followed and the trade entered a rare boom period.